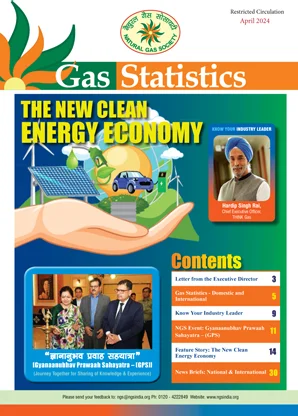

GAS STATISTICS REVIEW Apr 2024) (**)

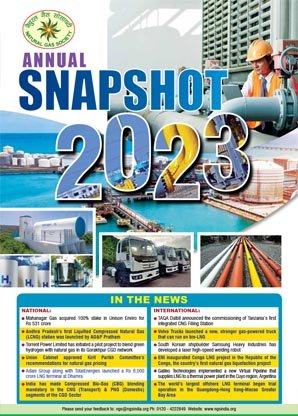

ANNUAL SNAPSHOT

Annual Snapshot 2023 || DIGITAL

Annual Snapshot 2023 || DIGITAL

UPCOMING EVENTS

FUTURE ENERGY ASIA 2024

Powering a resilient and low carbon energy future

15 – 17 MAY 2024, Queen Sirikit National, Convention Center, Bangkok, Thailand

READ MORE

PAST EVENTS

Why every car owner should consider CNG conversion

In light of the recent increase in petrol prices, switching to compressed natural gas cannot only help car owners save money but also contribute to a more sustainable environment. This...

GAIL reduces CNG price by Rs 2.50 per kg in the country

The company said that the move aims to make CNG a more attractive option for consumers, encouraging the adoption of clean fuels and promoting sustainable transportation practices. NEW DELHI: Following...

GAIL organised CBG Workshop for stakeholders under aegis of MoPNG

Chandigarh: Under the aegis of Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, GAIL (India) Limited organized a CBG Workshop here which was attended by bank officers, LOI holders, Compressed Bio Gas (CBG) producers,...

Indicative Prices of crude oil, Brent, and Natural gas

Data source – https://tradingeconomics.

Top News From Gas Industry * * *

NATIONAL NEWS

LNG import volume up 17.5% in FY24 as consumption rises

While the fertilizer sector contributed to 32% of the total...

Indian Biogas Association joins hands with HAI to promote hydrogen

Indian Biogas Association (IBA) has partnered with Hydrogen Association of...

LNG import volume up 17.5% in FY24 as consumption rises

India’s import of liquefied natural gas (LNG) rose in volume...

INTERNATIONAL NEWS

FG To Launch CNG Initiative Before May 29

The Nigerian Government has announced the launch of the Compressed...

Morocco considers three regasification units

In addition to the announced regasification units in Nador port,...

Philippines nears comprehensive energy security with landmark LNG collaboration

The long-awaited aspiration of President Marcos, shared by the entire...